Day 9: Building a Production-Grade TCP Log Shipping Client

What We’re Building Today

By the end of this lesson, you’ll have implemented:

Resilient TCP log shipping client with automatic reconnection and exponential backoff

Buffered batch transmission to optimize network utilization and throughput

Circuit breaker integration preventing cascade failures when the server is unavailable

Distributed tracing pipeline from log generation through TCP transmission to Kafka ingestion

Production monitoring stack with Prometheus metrics and Grafana dashboards showing transmission rates, buffer depths, and failure modes

Why This Matters: The Hidden Complexity of Log Shipping

Every large-scale system generates logs. Netflix produces over 1 trillion events daily. Uber’s ML platform processes 100+ TB of logs per day. But here’s what they don’t tell you: the hardest part isn’t processing logs—it’s reliably getting them from A to B without losing data or crashing your application.

Log shipping is deceptively complex. When your application server crashes, you lose buffered logs. When network partitions occur, do you block the application or drop data? When the log receiver is overloaded, does your client retry forever, exhausting memory? These aren’t theoretical problems—they’re production incidents waiting to happen.

The pattern we’re building today—a resilient, buffered TCP client with graceful degradation—is the foundation of systems like AWS CloudWatch Logs, Datadog’s agent, and the Elastic Stack. Understanding these trade-offs separates engineers who can “make it work” from those who can “make it work at scale.”

System Design Deep Dive: Five Critical Patterns

Pattern 1: Buffering Strategy - Memory vs. Disk Trade-offs

The first architectural decision: where do we buffer logs before transmission?

In-memory buffering (our approach today) provides microsecond-level latency and trivial implementation. The trade-off? You lose logs on application crashes. For metrics and debug logs, this is acceptable—a 0.01% data loss rate is invisible in aggregate statistics.

Disk-backed buffering (Kafka producer pattern) guarantees durability but adds 5-20ms latency per write and complex failure modes (disk full, I/O errors). Financial transactions need this. Debug logs don’t.

Netflix uses memory buffers for 95% of their telemetry. Critical audit logs get disk backing. Know your use case.

Pattern 2: Batch Transmission - The Network Efficiency Pattern

Sending logs one-at-a-time creates 40+ bytes of TCP/IP overhead per log line. At 100K logs/second, that’s 4GB/day of pure header waste. Batching is non-negotiable at scale.

Our implementation uses a time-and-size-based flushing strategy:

Flush every 100ms OR when buffer reaches 100 messages

This balances latency (worst case 100ms delay) with efficiency

The critical insight: the flush interval is a tunable consistency parameter. Lower intervals mean fresher data but worse throughput. Datadog uses 10-second batches for metrics (they’re already delayed) but 100ms batches for traces (latency-sensitive).

Pattern 3: Connection Management - The Reconnection Loop

TCP connections fail. Networks partition. Servers restart. Your client must handle this without human intervention.

The anti-pattern is aggressive reconnection: trying to reconnect every 100ms creates thundering herd problems when a server restarts. 1000 clients hammering a server simultaneously can prevent it from ever becoming healthy.

Exponential backoff with jitter solves this:

delay = min(initial_delay * 2^attempt + random(0, 1000ms), max_delay)

This spreads reconnection attempts over time. When Amazon’s Route53 had an outage in 2012, services with proper backoff recovered in minutes. Services without it stayed down for hours due to self-inflicted load.

Pattern 4: Circuit Breaker - Failing Fast vs. Trying Forever

When the log receiver is down, should your client queue millions of logs in memory? This is the backpressure problem that crashes production systems.

A circuit breaker pattern (we use Resilience4j) provides three states:

CLOSED: Normal operation, logs flow through

OPEN: Server is down, reject logs immediately (preserving application memory)

HALF_OPEN: Testing if server recovered with limited traffic

The controversial decision: we drop logs when the circuit is open. This prioritizes application stability over log completeness. If you need 100% log delivery, you need disk-backed buffering and complex flow control—increasing system complexity by 10x.

Uber’s decision here is instructive: their core rider/driver matching system has a circuit breaker that drops non-critical logs under extreme load. Completing rides matters more than debug telemetry.

Pattern 5: Observability - Measuring What You Can’t See

How do you debug a distributed log shipping system? You instrument the instrumentation itself.

Our implementation exports metrics:

logs_sent_total: Track throughput and identify anomaliesbuffer_depth: Early warning for backpressure issuesconnection_failures_total: Network reliability indicatorcircuit_breaker_state: Know when you’re dropping logs

The key metric is buffer depth over time. If it’s steadily growing, you have a throughput mismatch—your application generates logs faster than your network can ship them. This is a leading indicator for system issues, often appearing 10-15 minutes before user-facing impact.

Lesson Video

Implementation Walkthrough: Building the TCP Client

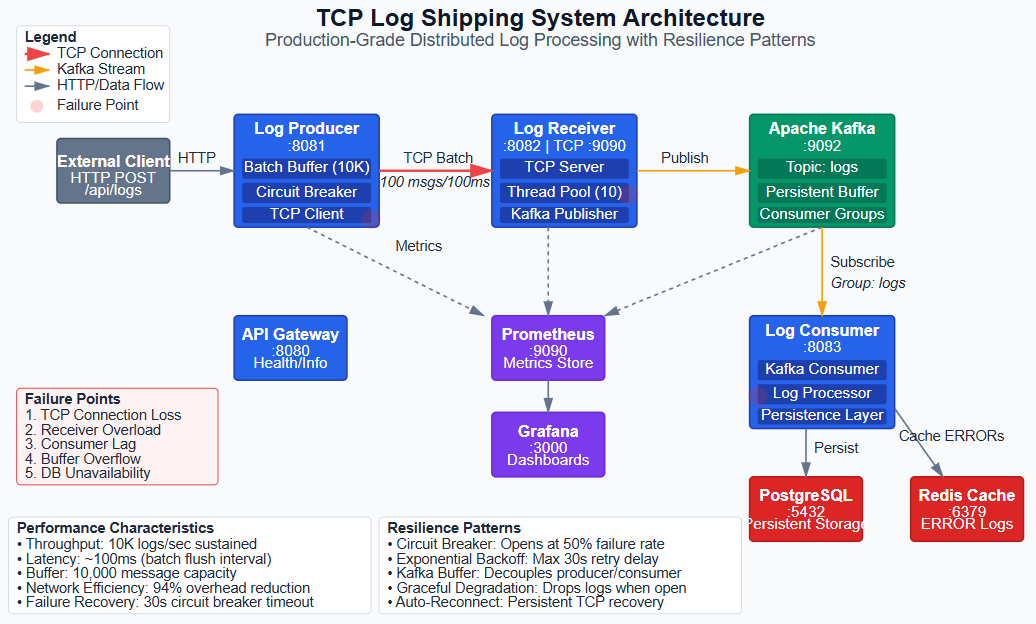

Our system has three components working together:

Log Producer Service generates application logs and ships them via TCP to the receiver. It implements buffering, batching, and circuit breaker patterns. The critical code is TcpLogShipperService:

@Scheduled(fixedRate = 100) // Flush every 100ms

public void flushBuffer() {

if (logBuffer.isEmpty()) return;

List<String> batch = new ArrayList<>();

logBuffer.drainTo(batch, batchSize);

circuitBreaker.executeSupplier(() -> {

sendBatch(batch);

return null;

});

}

The @Scheduled annotation creates a background thread that flushes every 100ms. drainTo() is an atomic operation that prevents race conditions. The circuit breaker wraps the transmission, automatically opening if the server is unhealthy.

Log Receiver Service accepts TCP connections and publishes logs to Kafka. It’s the bridge between the synchronous TCP world and the asynchronous streaming world. The server uses Spring’s ServerSocket with a thread pool:

while (running) {

Socket client = serverSocket.accept();

executorService.submit(() -> handleClient(client));

}

Each connection gets its own thread. For production systems with thousands of clients, you’d use NIO (non-blocking I/O) or Netty. But for log shipping with 10-100 clients, thread-per-connection is simpler and sufficient.

Log Consumer Service reads from Kafka and persists to PostgreSQL. This demonstrates the decoupling pattern—the producer and consumer are completely independent. The consumer can be offline for hours, and logs safely queue in Kafka.

The architectural decision here: we use Kafka as a buffer, not just a transport. This means even if PostgreSQL is down, logs keep flowing. When it recovers, the consumer catches up. This is the difference between “coupled” and “decoupled” architectures.